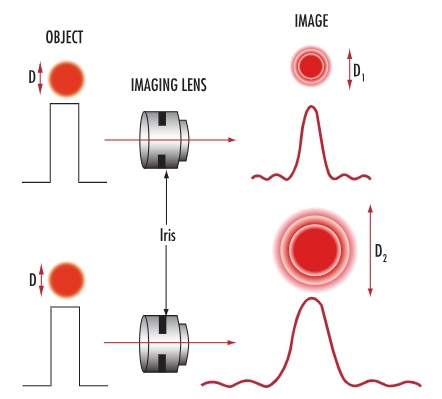

Machine vision practitioners, regardless of application or lens type, know that contrast is essential. Without sharp definition, features cannot be detected effectively.

When using a telecentric lens for precision optical 2-D measurements, ideally one should also use collimated lighting. Per the old adage about a chain being only as good as its weakest link, why invest in great lensing and then cut corners on lighting?

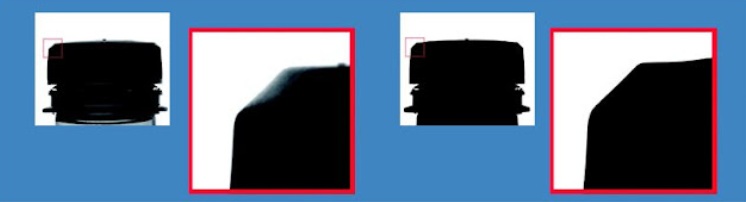

WITH collimated light expect high edge definition:

The cost of the light typically pays for itself relative to quality outcomes. Below see red-framed enlargements of the same region of a part being imaged by the same telecentric lens.

The left-hand image was taken with a conventional backlight – note how the light wraps around the edge, creating “confusion” and imprecision due to refracted light coming from all angles.

The right-hand image was obtained with a collimated backlight – with excellent edge definition.

It all comes down to resolution

While telecentric imaging is a high-performance subset of the larger machine vision field in general, the same principles of resolution apply. It takes several pixels to confidently resolve any given feature – such as an edge – so any “gray areas” induced by lower quality lighting or optics would drag down system performance. See our blog and knowledge-base coverage of resolution for more details.

Collimated lighting in more detail

Above we see the results of using “diffuse” vs. “collimated” light sources, which are compelling. But what is a collimated light and how does it work so effectively?

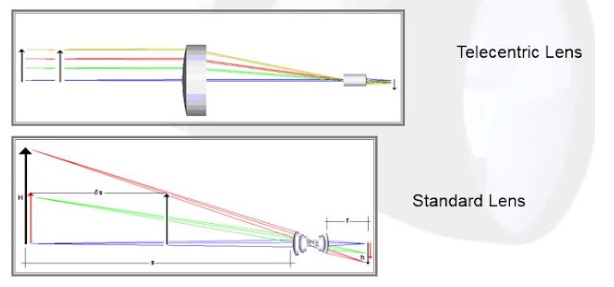

UNLIKE a diffuse backlight, whose rays emanate towards the object at angles ranging from 0 to almost 180°, a collimated backlight sends rays with only very small deviations from perfectly parallel. Since parallel rays are also all that the telecentric lens receives and transmits on to the camera sensor, stray rays are mitigated and essentially eliminated.

The result is a high-contrast image which is easier to process with high-reliability. Furthermore, shutter speeds are typically faster, achieving necessary saturation more quickly, thereby shortening cycle times and increasing overall throughput.

Many lights to choose from:

The video below shows a range of light types and models, including clearly labeled direct, diffuse, and collimated lights.

[Optional] Telecentric concepts overview

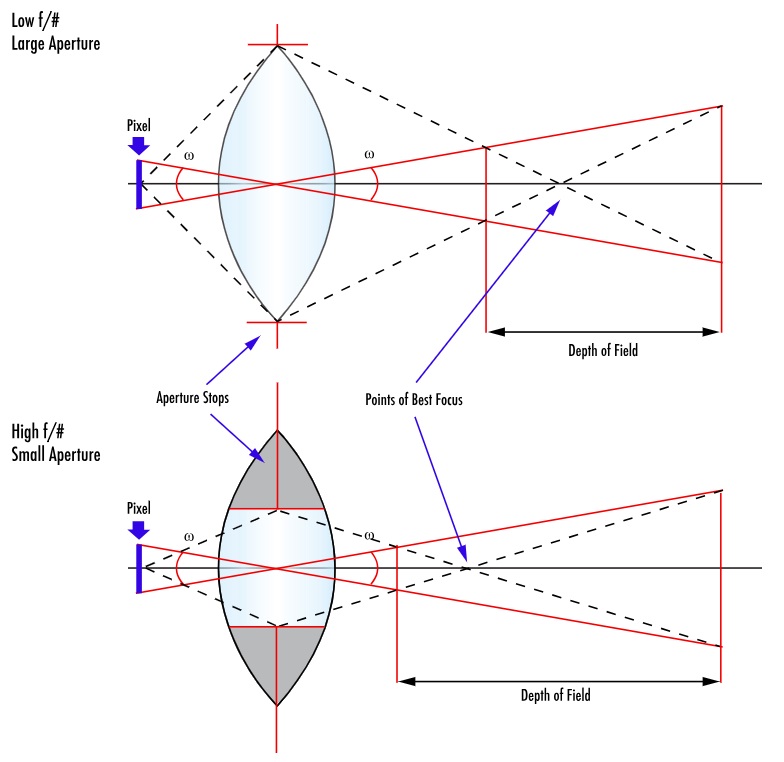

Below please compare the diagrams that show how light rays travel from the target position on the left, through the respective lenses, and on to the sensor position on the far right.

A telecentric lens is designed to insure that the chief rays remain parallel to the optical axis. The key benefit is that (when properly focused and aligned) the system is invariant to the distance of the object from the lens. This effectively ignores light rays coming from other angles of incidence, and thereby supports precise optical measurement systems – a branch of metrology.

If you’d like to go deeper on telecentrics, see the following two resources:

Telecentric concepts presented as a short blog.

Alternatively as a more comprehensive Powerpoint from our KnowledgeBase.

Video: Selecting a telecentric lens:

Call us at 978-474-0044 to tell us more about your application – and how we can guide you through telecentric lensing and lighting options.

1st Vision’s sales engineers have over 100 years of combined experience to assist in your camera and components selection. With a large portfolio of cameras, lenses, cables, NIC cards and industrial computers, we can provide a full vision solution!

About you: We want to hear from you! We’ve built our brand on our know-how and like to educate the marketplace on imaging technology topics… What would you like to hear about?… Drop a line to info@1stvision.com with what topics you’d like to know more about.